Those who sneer that mass-appeal genre fiction doesn’t qualify as “literature” show an ignorance of history. Many classics—the Rāmāyaņa and the Mahābhārata, the Iliad and the Odyssey, the Bible—contain monsters and demons, heroes with superhuman powers, virgin births, and half-divine humans. Whether the snobs like it or not, these are works of fantasy that earned immortality because of their popularity with the masses.

One of the oldest works of literature, perhaps the oldest of all, is the epic poem Gilgamesh. Like the classics listed above, Gilgamesh is rooted in history, was passed down orally at first, and is filled with supernatural and fantastical elements, starting with King Gilgamesh himself, who is nine feet tall and never needs to sleep.

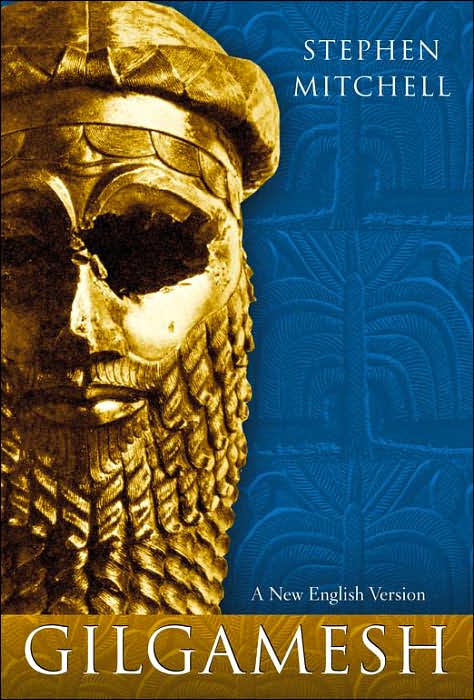

I’ll blog later on the fantastical elements in Gilgamesh and on the similarities between the legends of Gilgamesh and of John Henry (of steel-driving fame). Today, for those unfamiliar with Gilgamesh, I’ll give a brief description of a work every writer should know about, using a recent English version of Gilgamesh by Stephen Mitchell as my primary source.

The historical King Gilgamesh ruled the city-state of Uruk in ancient Sumer about 2750 BCE. Then, Uruk was the largest city in the world; today, it is called Warka and lies in ruins 155 miles south of Baghdad in Iraq.

The earliest texts (clay tablets) we have date from about 2100 BCE and are separate stories about Gilgamesh. Later, these and other stories were integrated into a coherent epic, which itself changed over the centuries. The so-called Standard Version was written by the priest Sîn-lēqi-unninni in about 1200 BCE. The epic exists only on broken tablets with missing pieces, so pure translations are impossible. That’s why Mitchell’s book is an “English version” and not an “English translation.”

King Gilgamesh is a great man with great flaws. He abuses his citizens until the gods decide he needs a match to temper him. The gods create Enkidu the wild man, who lives among the animals. Gilgamesh hears of Enkidu and sends a priestess of Ishtar to tame him and bring him back to Uruk. Shamhat the priestess starts by seducing Enkidu. Once Enkidu loses his innocence, his animal friends flee and he must abandon his forest ways. Shamhat then teaches him how to eat, dress, bathe, and wash his hair (some things never change) and he becomes fully human. She takes him back to Uruk, where he challenges Gilgamesh to a fight, which Gilgamesh wins. Enkidu becomes Gilgamesh’s best friend, lover, and later his adopted brother.

To become so famous that his name will live forever, Gilgamesh travels thousands of miles on foot to the sacred Cedar Forest, Enkidu at his side. The king intends to kill the fearsome creature that guards the forest. When Gilgamesh defeats the creature, it begs for mercy, and Gilgamesh is tempted to spare it. Enkidu, however, eggs him on, and Gilgamesh hacks at the creature’s neck with his axe until it is dead. The two then indulge in an orgy of forest destruction, cutting down every sacred tree (again, some things never change—although because cars have not yet been invented, they at least do not put up a parking lot).

After they return from to Uruk, Gilgamesh takes a bath and dresses up. He must clean up pretty good, because the goddess Ishtar falls madly in lust with him. She offers him presents to marry her, but Gilgamesh rejects and insults her. The furious goddess sends the Bull of Heaven to kill Gilgamesh. After the Bull causes famine and kills hundreds of warriors, Enkidu and Gilgamesh kill it. To add insult to injury, Enkidu rips off a chunk of the Bull’s leg and throws it in Ishtar’s face.

After they return from to Uruk, Gilgamesh takes a bath and dresses up. He must clean up pretty good, because the goddess Ishtar falls madly in lust with him. She offers him presents to marry her, but Gilgamesh rejects and insults her. The furious goddess sends the Bull of Heaven to kill Gilgamesh. After the Bull causes famine and kills hundreds of warriors, Enkidu and Gilgamesh kill it. To add insult to injury, Enkidu rips off a chunk of the Bull’s leg and throws it in Ishtar’s face. The gods then hold a council. Angry that the two "heroes" have killed the guardian of the Cedar Forest and the Bull of Heaven, they decide one must die. They choose Enkidu. He endures twelve days of agony before succumbing. Gilgamesh goes mad with grief and heads into the wilderness with matted hair and wearing a lion skin.

Gilgamesh becomes terrified of dying. He heads toward the supernatural land where Utnapishtim lives, the only immortal man. He endures many trials and hardships before he reaches the garden of the gods. There, his ravaged, frost-bitten, sunburned, hollow-cheeked face scares the tavernkeeper so much that she climbs onto her roof, from where she shouts down advice to Gilgamesh to go home and eat, drink, and be merry until it’s time to die. When he ignores her suggestions, she relents and tells him how to find Utnapishtim’s boatman.

Not having learned anything from his previous adventures, Gilgamesh finds the boatman and promptly hacks his entire crew into pieces with his axe. Then the boatman tells him that the crew was needed to cross the Waters of Death to reach Utnapishtim. Oops. Perhaps fearing he will share his crew's fate, the boatman conceives a scheme to cross the Waters of Death without harm. The idea works.

Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh how the gods once decided to destroy the earth with a huge flood. The god Ea, however, let Utnapishtim in on the secret and counseled him to build a huge ship and load it with examples of every living creature. He did so. The rain poured for six days and seven nights and killed every living thing. Utnapishtim’s story then proceeds much like Noah’s until the end, when the gods make him and his wife immortal.

Utnapishtim sets Gilgamesh a test to see whether he is worthy of being immortal, which he fails. Utnapishtim sends Gilgamesh away, but at his wife’s urging first tells him of a plant that grows underwater that will make him eternally youthful. Gilgamesh finds the plant. Cautious for the first time, he decides to take it home and test it on an old man before eating the plant himself. Alas, when he sets the plant down to take a bath, a snake carries it off.

Gilgamesh returns to Uruk emptyhanded. But as he looks at Uruk and describes its beauty, one imagines that Gilgamesh at last realizes how fortunate he is and will live and rule more wisely than before (admittedly not a very high bar to meet).

4 comments:

I agree with you that fantasy and mythology are an indelible part of literature and their influence and reinterpretation is found all over contemporary literature and in film. The Greek myths are probably the best known examples, but there are many others. When I read your post, I immediately thought of Beowulf, an epic poem that has been reinterpreted and studied by some of our most prominent literary icons, most notably J.R.R. Tolkien and John Gardner. I believe there is much to be learned from these epic tales. I aspire to create contemporary fiction, but look to myth and legend often for inspiration. Thank you for introducing me to Gilgamesh -- the name sounded immediately familiar, but I am sure I never heard the tale before now.

You seem so prolific!

Best wishes

In an essay I did on heroic fantasy I argued that the genre traced back to Gilgamesh. It's certainly interesting reading. I didn't know much about the real Uruk so thanks for that information. You're absolutely right that people who downplay fantasy don't realize that it's the oldest form of written fiction there is.

LISA, You are probably already familiar with Joseph Campbell’s analyses of storytelling constants around the world and through the ages, but in case you aren’t, you might be interested in Christopher Vogler’s book The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 2nd edition. It’s about using “the principles of myth to create masterful stories that are dramatic, entertaining, and psychologically true” (according to the back cover blurb). He draws his examples from popular movies.

McEwen, Thanks for stopping by!

Charles, If you haven't read Stephen Mitchell's new version, you might want to. It's quite different from other versions and has a lot of interesting backstory and footnotes. I hadn't read any Gilgamesh since college, and I was pleased to find that scholars have more of the text to work with now.

Post a Comment