Uncounted civilizations have sprouted, flourished, and crumbled into dust since the first pieces of Gilgamesh were composed. Yet it has lessons for the modern writer. The epic shows that some elements of literature have roots thousands of years in the past and thus may have universal appeal to the human psyche:

Uncounted civilizations have sprouted, flourished, and crumbled into dust since the first pieces of Gilgamesh were composed. Yet it has lessons for the modern writer. The epic shows that some elements of literature have roots thousands of years in the past and thus may have universal appeal to the human psyche:The quest. Like many modern fantasies, Gilgamesh is a quest story. Probably because it was compiled from several independent stories, it contains not one quest, but several. Although King Gilgamesh’s main quest is to find Utnapishtim to learn the secret of eternal life, he also journeys to the Cedar Forest to kill the monster that guards it, saves the city of Uruk by defeating the Bull of Heaven, and seeks the plant that grants eternal life. In addition, the priestess Shamhat travels three days into the wilderness to find and civilize Enkidu the wild man, and Enkidu’s destiny requires that he make a quest to Uruk to find and fight Gilgamesh.

Reworking of old legends and myths. Just as Bram Stoker’s Dracula was based on old folktales and legends and then itself inspired innumerable books, Gilgamesh was constructed from several ancient legends about a historic king and is the basis for later tales. For example, the story of Noah in Genesis chapters 5–8 was based on the story of Utnapishtim, which was itself based on a massive flood of Mesopotamia that geologists date to about 5600 BCE.

Complex, larger-than-life protagonists. The beginning of the epic, describing Gilgamesh, says that

Complex, larger-than-life protagonists. The beginning of the epic, describing Gilgamesh, says that“The city is his possession, he struts through it arrogant, his head raised high, trampling its citizens like a wild bull. He is king, he does whatever he wants, takes the son from his father and crushes him, takes the girl from her mother and uses her, the warrior’s daughter, the young man’s bride, he uses her, no one dares to oppose him.”

(quote from Stephen Mitchell’s English version)

At that point, I was already rooting for his opponents!

However, Gilgamesh is also described as “beloved by his soldiers,” “splendid,” “radiant,” “perfect,” and loved by Shamash, the sun god. Despite his tyranny, his city shines with prosperity: The young men dress in brilliant colors and fringed shawls, the priestesses chat and laugh, and “Every day is a festival in Uruk, with people singing and dancing in the streets, musicians playing their lyres and drums....”

Gilgamesh incorporates both good and evil in himself at the beginning and at the end. The story never passes judgment on his acts, letting them speak for themselves. Although Gilgamesh never apologizes for or regrets his many evil deeds, he does partially redeem himself after returning home from his quest: He rebuilds temples that the Great Flood had destroyed, revives forgotten religious rituals, and renews laws “for the welfare of the people and the sacred land.”

Exploration of the meaning of life and death. Gilgamesh at the start of his adventures is already a hero and undefeated warrior, king of the largest city in the world, two-thirds divine (the epic does not explain this strange fact), and the strongest man in the world. Yet he is not happy until he meets Enkidu, who becomes his best friend, lover, and stepbrother. Once Enkidu dies, Gilgamesh’s life is without purpose. How can one live, knowing that death awaits? He casts off his kingly clothes to wander the wilderness dressed in a lion skin.

Gilgamesh thinks the solution is to become immortal. But the answer has already been hinted at in his relationship with Enkidu and is stated outright later by both the tavernkeeper and Utnapishtim. The tavernkeeper says it best:

“Humans are born, they live, then they die, this is the order that the gods have decreed. But until the end comes, enjoy your life, spend it in happiness, not despair. Savor your food, make each of your days a delight, bathe and anoint yourself, wear bright clothes that are sparkling clean, let music and dancing fill your house, love the child who holds you by the hand, and give your wife pleasure in your embrace. That is the best way for a man to live.”

Surprise endings. Gilgamesh is constructed like a snake swallowing its tail. At the epic’s end, Gilgamesh tells the boatman about the glories of Uruk—and he uses the very words that start the tale. One suddenly realizes that the third-person anonymous narrator of Gilgamesh’s story has been Gilgamesh himself!

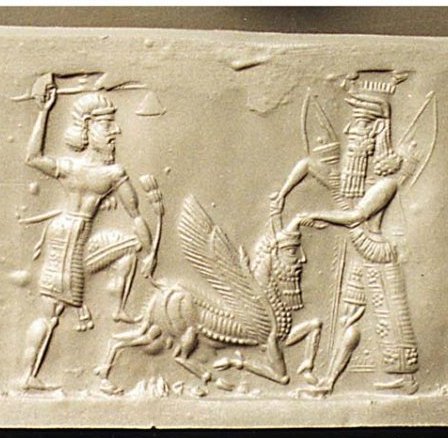

Marvels and wonders. Gilgamesh contains an ocean whose waters kill when touched, men made of stone, a flood that drowns everything as far as the eye can see (not a fantastical element for us New Orleanians), a man who lives with wild animals, a bush whose leaves make one eternally young, scorpion people, monsters, and other treats to delight the imagination. My favorite was the garden of the gods with “trees that grew rubies, trees with lapis lazuli flowers, trees that dangled gigantic coral clusters like dates.”

However, Gilgamesh makes clear that some elements of literature are culture specific, such as what makes a character heroic and sympathetic. In the epic, Gilgamesh is a major jerk. For today’s readers, Gilgamesh’s outbreaks of inexplicable violence (and, much more recently, those of the knights of the Round Table in Thomas Malory’s Le Mort d’Arthur) are baffling and verge on pathological behavior. Yet in ancient times people considered him such a great man that stories were told of him for at least 1500 years.

Tired yet of Gilgamesh? I hope not, because next week I’ll blog about him and John Henry and speculate how a man becomes a legend.

6 comments:

Shauna, you are a wonderful teacher. I'm as hooked on Gilgamesh as I was on The Sopranos -- and probably for some of the same reasons! I will be tuning in next week for more.

LISA, I'm glad you're enjoying the Gilgamesh posts. I sure am enjoying writing them. Since high school I have been fascinated by how much of modern culture has roots in ancient Sumer, a country most Americans have probably never heard of.

Like you, not far into Gilgamesh I was hoping to see him get brought down.

I also loved the "wonders" part.

It's interesting to me that some writers still today in fantasy create Gilgamesh type heroes, because I don't tend to like that type of hero myself and don't root for him.

On the other hand, I love that the fantasy tradition still has the "wonders" as an intrigal part.

CHARLES, it's not just fantasy that still uses Gilgamesh-type heroes. They are even more popular in the romance genre, where they are called "alpha male heroes" and populate most of the books.

Although I usually avoid romances with that kind of hero, I've read enough of them to know that these guys often meet their match in the heroine, who turns them into someone sympathetic by the end (playing into the common female fantasy of taking the man you get and turning him into the man you want instead of looking for the man you want in the first place).

Shauna, thanks for these fascinating posts on the Epic of Gilgamesh. Although I read about the Epic in both history and literature courses in college (lo, many years ago), I've never read the Epic itself. Your posts have tempted me to try it. I'll look for it...heck, I wonder if I can download it from somewhere online. (Definitely no copyright on that, eh? Except maybe for a recent translation.)

SPINX INKm I suspect you're right, that you can find Gilgamesh online, perhaps even several versions of it. I find, though, with ancient literature that the skill of the translator or interpretor makes a big difference in my enjoyment (or lack thereof).

Post a Comment