Award-winning author

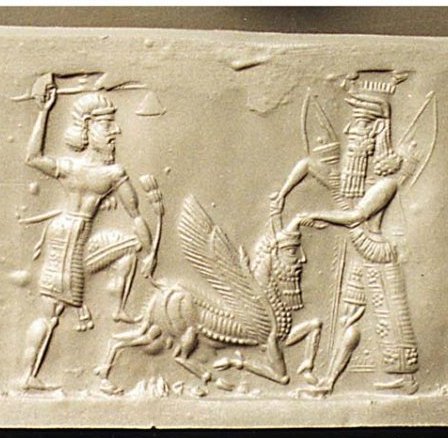

The "Standard of Ur" from ancient Mesopotamia

28 July 2007

Off the 'Net for a while...

I have some business to attend to, so my next post won't be until August 10th or later. See you then!

25 July 2007

Tribute to Peter Banks, mentor and friend

Just last year, writer, editor, and publisher Peter Banks (1955–2007) seemed at the top of his career. Not only did he found Banks Publishing, a publications consulting and services firm, but Folio Magazine also honored him as one of the 40 most influential people in magazine publishing.

Today, people gathered in Virginia at his memorial service. He died Saturday, peacefully and in no pain.

Peter spent most of his career at the American Diabetes Association (ADA), but I first met him when we both worked at The Journal of NIH Research, a start-up magazine targeted at biomedical researchers. He was the production manager; I came on as 1/2 production assistant, 1/2 writer. This was in the good old days when production was like kindergarten—you cut up copy and photocopies of photos and artwork and pasted them down on layout sheets with wax. We got to be friends as we sat side by side, laying out pages, with him instructing me in the essentials of good page design. He also helped teach me how to write a magazine article. (I got hired as a writer at JNIHR because I could get up to speed quickly on complex biomedical instrumentation and techniques, but my most complex published writing before then was cookbook reviews for the Iowa City New Pioneer Co-op Newsletter. Obviously, I had a lot to learn.)

Peter spent most of his career at the American Diabetes Association (ADA), but I first met him when we both worked at The Journal of NIH Research, a start-up magazine targeted at biomedical researchers. He was the production manager; I came on as 1/2 production assistant, 1/2 writer. This was in the good old days when production was like kindergarten—you cut up copy and photocopies of photos and artwork and pasted them down on layout sheets with wax. We got to be friends as we sat side by side, laying out pages, with him instructing me in the essentials of good page design. He also helped teach me how to write a magazine article. (I got hired as a writer at JNIHR because I could get up to speed quickly on complex biomedical instrumentation and techniques, but my most complex published writing before then was cookbook reviews for the Iowa City New Pioneer Co-op Newsletter. Obviously, I had a lot to learn.)When Peter left JNIHR to become head of publications for ADA and I left to become a freelance writer, he often directed work my way. Because of him, I copyedited for the medical journal Diabetes Care for a while, was the editor/writer/layout artist for The Diabetes Advisor newsletter during its six-year existence, and wrote for ADA a variety of patient education pamphlets and booklets, advertorials, a book, and many articles in the patient magazine Diabetes Forecast. He became busier and busier at ADA, particularly after he became publisher, but continued to help me out.

I still keep by my desk a fax he sent me on November 23, 1993. I was, shall we say, not the most skilled or talented person at titling my articles. Peter talked to me about it a few times, but when my titles continued to be boring, he faxed me a list called “Ten Simple Steps To Catchy Coverlines Now!” Fourteen years later, I still use that list to help me come up with titles. (I’ll post that list another week for your enjoyment and use.)

Even after he became sick this spring, he remained a teacher to others through his thoughtful and often humorous blog about having cancer at the CaringBridge site. If you have the time, it’s worth a trip there to read it.

Farewell, Peter, and thank you. My medical writing career would not have been nearly as successful without your help.

18 July 2007

Man into myth

The infant Hercules strangled two poisonous snakes while in the cradle. Baby John Henry, not to be outdone, hefted a hammer and proclaimed “Hammer’s gonna be the death of me,” or so one version of the ballad “John Henry” says.

The history behind that ballad is the subject of a fascinating 2006 book, Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend by history professor Scott Reynolds Nelson. Dr. Nelson first recounts his efforts to find the historic John Henry and then traces how the story of this obscure railroad worker mutated over time and spread across the country. Eventually, John Henry (after undergoing a race change) became the inspiration for Superman and Captain America, and the legend of how this colossus beat the steam drill is known by nearly every American.

The history behind that ballad is the subject of a fascinating 2006 book, Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend by history professor Scott Reynolds Nelson. Dr. Nelson first recounts his efforts to find the historic John Henry and then traces how the story of this obscure railroad worker mutated over time and spread across the country. Eventually, John Henry (after undergoing a race change) became the inspiration for Superman and Captain America, and the legend of how this colossus beat the steam drill is known by nearly every American.But it didn’t happen quite the way you think. Here, according to Dr. Nelson, is the story of John Henry.

John Henry was 5 feet, 1.25 inches tall at age 19, when he was arrested for taking something from a store in 1866—not the muscleman of legend at all. Justice for black people was harsh in post-war Virginia, and his small crime earned him a big sentence, 10 years in the Virginia Penitentiary. The penitentiary sent him and other prisoners to work on the railroad. John Henry met his death tunneling through Lewis Mountain in Virginia for the Chesapeake and Ohio line, probably about 1873. If his contest with the steam drill hadn’t killed him, the dust from the excavation would have, for the silica in the rock scoured and scarred lungs. John Henry’s body was returned to the penitentiary for burial beside a large white building.

Gilgamesh and John Henry seem an unlikely pair—the king of the largest city in the world and a petty thief. Yet both became legends, and storytellers can benefit by thinking about the common elements of their stories. (Blog readers unfamiliar with the epic poem Gilgamesh might wish to read my blog entries of 6 July and 12 July before continuing.)

Gilgamesh and John Henry seem an unlikely pair—the king of the largest city in the world and a petty thief. Yet both became legends, and storytellers can benefit by thinking about the common elements of their stories. (Blog readers unfamiliar with the epic poem Gilgamesh might wish to read my blog entries of 6 July and 12 July before continuing.)- Both men lived in a culture with an oral (rather than written) tradition. As in the children’s game of telephone, each retelling had the potential to change the story. No wonder multiple versions exist of both legends.

- The stories weren’t created, but accreted. Gilgamesh is a pastiche of several older stories about Gilgamesh and Utnapishtim; phrases in and the structure of some versions of “John Henry” come from old British ballads.

- Both are suprahuman in their legends. Gilgamesh reportedly stood nine feet tall and never needed sleep, whereas John Henry prognosticated as a baby and was remembered as a huge, muscled man.

- Their stories don’t just entertain. They contain important lessons. Gilgamesh is about the abuse of power, what it means to be civilized, and how to live a meaningful life. “John Henry” was originally, according to Dr. Nelson, a cautionary story repeated to remind railroad workers to pace themselves. Later it became a story of the power of perseverance.

- The lessons are relevant to their culture. The first civilization in Sumer had no predecessors to learn from. Leaders and citizens were making it up as they went along. Gilgamesh preserves what they learned for later civilizations, which clearly valued the lessons. “John Henry” spoke not only to black prisoners working on the railroad but also to their free white counterparts, later to the black and white coal miners in the Appalachians who ruined their health to feed the insatiable maws of train engines, and later yet to all oppressed workers and those who saw the Machine Age change their world into something unrecognizable and frightening.

- Both were men who believed in themselves and did the impossible. Gilgamesh killed various supernatural creatures and traveled to places no normal human had ever gone. John Henry sunk a fourteen-foot pilot hole for blasting while the steam drill went a pitiful nine feet.

Are any of my characters worthy of such immortality? Too few, I fear.

How about yours? It’s a question worth asking. If ancient Sumer and chain gangs seem far removed from your characters, think about the stories that have been passed down in your family. Ordinary people did something extraordinary—perhaps something as simple as performing a deed of great kindness or making a particularly cruel joke—and the tales live on, even after their deaths.

I suggest we as writers can make our characters more compelling by subjecting them to the John Henry test: Will anyone remember them after they are gone?

12 July 2007

What modern writers can learn from Gilgamesh

Though the so-called Standard Version of Gilgamesh was inscribed into clay tablets 3200 years ago, any modern speculative fiction reader would recognize it immediately as a fantasy. There’s a quest to pursue, monsters to be fought, and supernatural wonders to see along the way. (Blog readers unfamiliar with Gilgamesh might wish to read my blog entry of 6 July before continuing.)

Uncounted civilizations have sprouted, flourished, and crumbled into dust since the first pieces of Gilgamesh were composed. Yet it has lessons for the modern writer. The epic shows that some elements of literature have roots thousands of years in the past and thus may have universal appeal to the human psyche:

Uncounted civilizations have sprouted, flourished, and crumbled into dust since the first pieces of Gilgamesh were composed. Yet it has lessons for the modern writer. The epic shows that some elements of literature have roots thousands of years in the past and thus may have universal appeal to the human psyche:

The quest. Like many modern fantasies, Gilgamesh is a quest story. Probably because it was compiled from several independent stories, it contains not one quest, but several. Although King Gilgamesh’s main quest is to find Utnapishtim to learn the secret of eternal life, he also journeys to the Cedar Forest to kill the monster that guards it, saves the city of Uruk by defeating the Bull of Heaven, and seeks the plant that grants eternal life. In addition, the priestess Shamhat travels three days into the wilderness to find and civilize Enkidu the wild man, and Enkidu’s destiny requires that he make a quest to Uruk to find and fight Gilgamesh.

Reworking of old legends and myths. Just as Bram Stoker’s Dracula was based on old folktales and legends and then itself inspired innumerable books, Gilgamesh was constructed from several ancient legends about a historic king and is the basis for later tales. For example, the story of Noah in Genesis chapters 5–8 was based on the story of Utnapishtim, which was itself based on a massive flood of Mesopotamia that geologists date to about 5600 BCE.

Complex, larger-than-life protagonists. The beginning of the epic, describing Gilgamesh, says that

Complex, larger-than-life protagonists. The beginning of the epic, describing Gilgamesh, says that

At that point, I was already rooting for his opponents!

However, Gilgamesh is also described as “beloved by his soldiers,” “splendid,” “radiant,” “perfect,” and loved by Shamash, the sun god. Despite his tyranny, his city shines with prosperity: The young men dress in brilliant colors and fringed shawls, the priestesses chat and laugh, and “Every day is a festival in Uruk, with people singing and dancing in the streets, musicians playing their lyres and drums....”

Gilgamesh incorporates both good and evil in himself at the beginning and at the end. The story never passes judgment on his acts, letting them speak for themselves. Although Gilgamesh never apologizes for or regrets his many evil deeds, he does partially redeem himself after returning home from his quest: He rebuilds temples that the Great Flood had destroyed, revives forgotten religious rituals, and renews laws “for the welfare of the people and the sacred land.”

Exploration of the meaning of life and death. Gilgamesh at the start of his adventures is already a hero and undefeated warrior, king of the largest city in the world, two-thirds divine (the epic does not explain this strange fact), and the strongest man in the world. Yet he is not happy until he meets Enkidu, who becomes his best friend, lover, and stepbrother. Once Enkidu dies, Gilgamesh’s life is without purpose. How can one live, knowing that death awaits? He casts off his kingly clothes to wander the wilderness dressed in a lion skin.

Gilgamesh thinks the solution is to become immortal. But the answer has already been hinted at in his relationship with Enkidu and is stated outright later by both the tavernkeeper and Utnapishtim. The tavernkeeper says it best:

Surprise endings. Gilgamesh is constructed like a snake swallowing its tail. At the epic’s end, Gilgamesh tells the boatman about the glories of Uruk—and he uses the very words that start the tale. One suddenly realizes that the third-person anonymous narrator of Gilgamesh’s story has been Gilgamesh himself!

Marvels and wonders. Gilgamesh contains an ocean whose waters kill when touched, men made of stone, a flood that drowns everything as far as the eye can see (not a fantastical element for us New Orleanians), a man who lives with wild animals, a bush whose leaves make one eternally young, scorpion people, monsters, and other treats to delight the imagination. My favorite was the garden of the gods with “trees that grew rubies, trees with lapis lazuli flowers, trees that dangled gigantic coral clusters like dates.”

However, Gilgamesh makes clear that some elements of literature are culture specific, such as what makes a character heroic and sympathetic. In the epic, Gilgamesh is a major jerk. For today’s readers, Gilgamesh’s outbreaks of inexplicable violence (and, much more recently, those of the knights of the Round Table in Thomas Malory’s Le Mort d’Arthur) are baffling and verge on pathological behavior. Yet in ancient times people considered him such a great man that stories were told of him for at least 1500 years.

Tired yet of Gilgamesh? I hope not, because next week I’ll blog about him and John Henry and speculate how a man becomes a legend.

Uncounted civilizations have sprouted, flourished, and crumbled into dust since the first pieces of Gilgamesh were composed. Yet it has lessons for the modern writer. The epic shows that some elements of literature have roots thousands of years in the past and thus may have universal appeal to the human psyche:

Uncounted civilizations have sprouted, flourished, and crumbled into dust since the first pieces of Gilgamesh were composed. Yet it has lessons for the modern writer. The epic shows that some elements of literature have roots thousands of years in the past and thus may have universal appeal to the human psyche:The quest. Like many modern fantasies, Gilgamesh is a quest story. Probably because it was compiled from several independent stories, it contains not one quest, but several. Although King Gilgamesh’s main quest is to find Utnapishtim to learn the secret of eternal life, he also journeys to the Cedar Forest to kill the monster that guards it, saves the city of Uruk by defeating the Bull of Heaven, and seeks the plant that grants eternal life. In addition, the priestess Shamhat travels three days into the wilderness to find and civilize Enkidu the wild man, and Enkidu’s destiny requires that he make a quest to Uruk to find and fight Gilgamesh.

Reworking of old legends and myths. Just as Bram Stoker’s Dracula was based on old folktales and legends and then itself inspired innumerable books, Gilgamesh was constructed from several ancient legends about a historic king and is the basis for later tales. For example, the story of Noah in Genesis chapters 5–8 was based on the story of Utnapishtim, which was itself based on a massive flood of Mesopotamia that geologists date to about 5600 BCE.

Complex, larger-than-life protagonists. The beginning of the epic, describing Gilgamesh, says that

Complex, larger-than-life protagonists. The beginning of the epic, describing Gilgamesh, says that“The city is his possession, he struts through it arrogant, his head raised high, trampling its citizens like a wild bull. He is king, he does whatever he wants, takes the son from his father and crushes him, takes the girl from her mother and uses her, the warrior’s daughter, the young man’s bride, he uses her, no one dares to oppose him.”

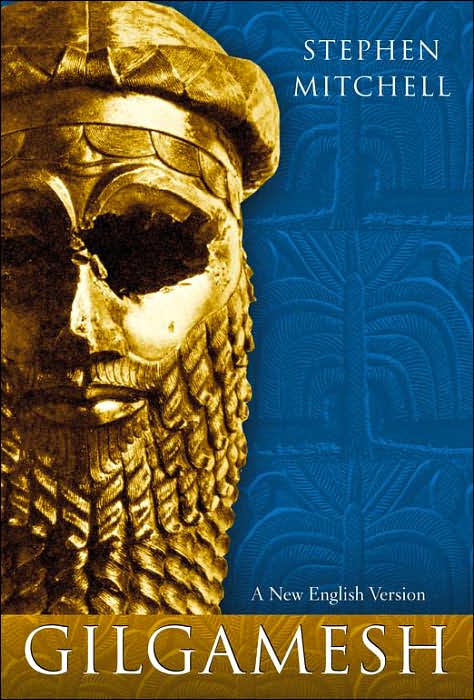

(quote from Stephen Mitchell’s English version)

At that point, I was already rooting for his opponents!

However, Gilgamesh is also described as “beloved by his soldiers,” “splendid,” “radiant,” “perfect,” and loved by Shamash, the sun god. Despite his tyranny, his city shines with prosperity: The young men dress in brilliant colors and fringed shawls, the priestesses chat and laugh, and “Every day is a festival in Uruk, with people singing and dancing in the streets, musicians playing their lyres and drums....”

Gilgamesh incorporates both good and evil in himself at the beginning and at the end. The story never passes judgment on his acts, letting them speak for themselves. Although Gilgamesh never apologizes for or regrets his many evil deeds, he does partially redeem himself after returning home from his quest: He rebuilds temples that the Great Flood had destroyed, revives forgotten religious rituals, and renews laws “for the welfare of the people and the sacred land.”

Exploration of the meaning of life and death. Gilgamesh at the start of his adventures is already a hero and undefeated warrior, king of the largest city in the world, two-thirds divine (the epic does not explain this strange fact), and the strongest man in the world. Yet he is not happy until he meets Enkidu, who becomes his best friend, lover, and stepbrother. Once Enkidu dies, Gilgamesh’s life is without purpose. How can one live, knowing that death awaits? He casts off his kingly clothes to wander the wilderness dressed in a lion skin.

Gilgamesh thinks the solution is to become immortal. But the answer has already been hinted at in his relationship with Enkidu and is stated outright later by both the tavernkeeper and Utnapishtim. The tavernkeeper says it best:

“Humans are born, they live, then they die, this is the order that the gods have decreed. But until the end comes, enjoy your life, spend it in happiness, not despair. Savor your food, make each of your days a delight, bathe and anoint yourself, wear bright clothes that are sparkling clean, let music and dancing fill your house, love the child who holds you by the hand, and give your wife pleasure in your embrace. That is the best way for a man to live.”

Surprise endings. Gilgamesh is constructed like a snake swallowing its tail. At the epic’s end, Gilgamesh tells the boatman about the glories of Uruk—and he uses the very words that start the tale. One suddenly realizes that the third-person anonymous narrator of Gilgamesh’s story has been Gilgamesh himself!

Marvels and wonders. Gilgamesh contains an ocean whose waters kill when touched, men made of stone, a flood that drowns everything as far as the eye can see (not a fantastical element for us New Orleanians), a man who lives with wild animals, a bush whose leaves make one eternally young, scorpion people, monsters, and other treats to delight the imagination. My favorite was the garden of the gods with “trees that grew rubies, trees with lapis lazuli flowers, trees that dangled gigantic coral clusters like dates.”

However, Gilgamesh makes clear that some elements of literature are culture specific, such as what makes a character heroic and sympathetic. In the epic, Gilgamesh is a major jerk. For today’s readers, Gilgamesh’s outbreaks of inexplicable violence (and, much more recently, those of the knights of the Round Table in Thomas Malory’s Le Mort d’Arthur) are baffling and verge on pathological behavior. Yet in ancient times people considered him such a great man that stories were told of him for at least 1500 years.

Tired yet of Gilgamesh? I hope not, because next week I’ll blog about him and John Henry and speculate how a man becomes a legend.

06 July 2007

The world’s first work of literature was a fantasy

Those who sneer that mass-appeal genre fiction doesn’t qualify as “literature” show an ignorance of history. Many classics—the Rāmāyaņa and the Mahābhārata, the Iliad and the Odyssey, the Bible—contain monsters and demons, heroes with superhuman powers, virgin births, and half-divine humans. Whether the snobs like it or not, these are works of fantasy that earned immortality because of their popularity with the masses.

One of the oldest works of literature, perhaps the oldest of all, is the epic poem Gilgamesh. Like the classics listed above, Gilgamesh is rooted in history, was passed down orally at first, and is filled with supernatural and fantastical elements, starting with King Gilgamesh himself, who is nine feet tall and never needs to sleep.

I’ll blog later on the fantastical elements in Gilgamesh and on the similarities between the legends of Gilgamesh and of John Henry (of steel-driving fame). Today, for those unfamiliar with Gilgamesh, I’ll give a brief description of a work every writer should know about, using a recent English version of Gilgamesh by Stephen Mitchell as my primary source.

The historical King Gilgamesh ruled the city-state of Uruk in ancient Sumer about 2750 BCE. Then, Uruk was the largest city in the world; today, it is called Warka and lies in ruins 155 miles south of Baghdad in Iraq.

The earliest texts (clay tablets) we have date from about 2100 BCE and are separate stories about Gilgamesh. Later, these and other stories were integrated into a coherent epic, which itself changed over the centuries. The so-called Standard Version was written by the priest Sîn-lēqi-unninni in about 1200 BCE. The epic exists only on broken tablets with missing pieces, so pure translations are impossible. That’s why Mitchell’s book is an “English version” and not an “English translation.”

King Gilgamesh is a great man with great flaws. He abuses his citizens until the gods decide he needs a match to temper him. The gods create Enkidu the wild man, who lives among the animals. Gilgamesh hears of Enkidu and sends a priestess of Ishtar to tame him and bring him back to Uruk. Shamhat the priestess starts by seducing Enkidu. Once Enkidu loses his innocence, his animal friends flee and he must abandon his forest ways. Shamhat then teaches him how to eat, dress, bathe, and wash his hair (some things never change) and he becomes fully human. She takes him back to Uruk, where he challenges Gilgamesh to a fight, which Gilgamesh wins. Enkidu becomes Gilgamesh’s best friend, lover, and later his adopted brother.

To become so famous that his name will live forever, Gilgamesh travels thousands of miles on foot to the sacred Cedar Forest, Enkidu at his side. The king intends to kill the fearsome creature that guards the forest. When Gilgamesh defeats the creature, it begs for mercy, and Gilgamesh is tempted to spare it. Enkidu, however, eggs him on, and Gilgamesh hacks at the creature’s neck with his axe until it is dead. The two then indulge in an orgy of forest destruction, cutting down every sacred tree (again, some things never change—although because cars have not yet been invented, they at least do not put up a parking lot).

After they return from to Uruk, Gilgamesh takes a bath and dresses up. He must clean up pretty good, because the goddess Ishtar falls madly in lust with him. She offers him presents to marry her, but Gilgamesh rejects and insults her. The furious goddess sends the Bull of Heaven to kill Gilgamesh. After the Bull causes famine and kills hundreds of warriors, Enkidu and Gilgamesh kill it. To add insult to injury, Enkidu rips off a chunk of the Bull’s leg and throws it in Ishtar’s face.

After they return from to Uruk, Gilgamesh takes a bath and dresses up. He must clean up pretty good, because the goddess Ishtar falls madly in lust with him. She offers him presents to marry her, but Gilgamesh rejects and insults her. The furious goddess sends the Bull of Heaven to kill Gilgamesh. After the Bull causes famine and kills hundreds of warriors, Enkidu and Gilgamesh kill it. To add insult to injury, Enkidu rips off a chunk of the Bull’s leg and throws it in Ishtar’s face. The gods then hold a council. Angry that the two "heroes" have killed the guardian of the Cedar Forest and the Bull of Heaven, they decide one must die. They choose Enkidu. He endures twelve days of agony before succumbing. Gilgamesh goes mad with grief and heads into the wilderness with matted hair and wearing a lion skin.

Gilgamesh becomes terrified of dying. He heads toward the supernatural land where Utnapishtim lives, the only immortal man. He endures many trials and hardships before he reaches the garden of the gods. There, his ravaged, frost-bitten, sunburned, hollow-cheeked face scares the tavernkeeper so much that she climbs onto her roof, from where she shouts down advice to Gilgamesh to go home and eat, drink, and be merry until it’s time to die. When he ignores her suggestions, she relents and tells him how to find Utnapishtim’s boatman.

Not having learned anything from his previous adventures, Gilgamesh finds the boatman and promptly hacks his entire crew into pieces with his axe. Then the boatman tells him that the crew was needed to cross the Waters of Death to reach Utnapishtim. Oops. Perhaps fearing he will share his crew's fate, the boatman conceives a scheme to cross the Waters of Death without harm. The idea works.

Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh how the gods once decided to destroy the earth with a huge flood. The god Ea, however, let Utnapishtim in on the secret and counseled him to build a huge ship and load it with examples of every living creature. He did so. The rain poured for six days and seven nights and killed every living thing. Utnapishtim’s story then proceeds much like Noah’s until the end, when the gods make him and his wife immortal.

Utnapishtim sets Gilgamesh a test to see whether he is worthy of being immortal, which he fails. Utnapishtim sends Gilgamesh away, but at his wife’s urging first tells him of a plant that grows underwater that will make him eternally youthful. Gilgamesh finds the plant. Cautious for the first time, he decides to take it home and test it on an old man before eating the plant himself. Alas, when he sets the plant down to take a bath, a snake carries it off.

Gilgamesh returns to Uruk emptyhanded. But as he looks at Uruk and describes its beauty, one imagines that Gilgamesh at last realizes how fortunate he is and will live and rule more wisely than before (admittedly not a very high bar to meet).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)